Climate change poses current and increasing hazards to human health. As the planet warms, health risks are increasing, threatening not only individuals but also public health and the healthcare system.

Risk factors are felt across the globe. Air pollution and wildfire smoke worsen asthma and allergies and contribute to heart and lung diseases. Extreme heat can cause heart failure, heat-related illnesses, and even death. Drought leads to dust storms and Valley Fever, while flooding can create indoor mold and fungi. Changes in disease patterns increase the risk of Lyme disease, West Nile Virus, malaria, and encephalitis. Additionally, warmer waters lead to harmful algal blooms and more waterborne diseases.

Understandably, people are feeling climate change anxiety. Stress, depression, feelings of loss, and post-traumatic stress disorder are linked to rising temperatures, increasing greenhouse gas levels, rising sea levels, and more frequent extreme weather events.

The need to address these health concerns drove the theme of the 17th annual Rhode Island Emerging Areas of Science IDeA Symposium, “Health Effects of Environmental Change,” held on October 24th, 2024, at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University.

“It's obvious to all of us that our environment is changing in many different ways, and not the least of which is climate change,” said Sharon Rounds MD, principal investigator for Advance Rhode Island Clinical Translational Research (Advance RI-CTR), associate dean for translational science at the Warren Alpert Medical School, and professor of medicine, pathology, and laboratory medicine. “But in addition to climate change, there have also been changes in air and water quality. Microplastics are a ubiquitous problem, especially here in the Ocean State.”

The health costs of plastic

The world's production of plastic has skyrocketed from two million tons in 1950 to more than 450 million tons annually, of which 400 million tons each year is plastic waste. The durability that makes plastics desirable also means they never fully break down. Instead, they degrade into ever smaller pieces. Plastic particles smaller than 5 millimeters are microplastics, considered dangerous because they contain toxins that can be inhaled, absorbed, and accumulated in organs.

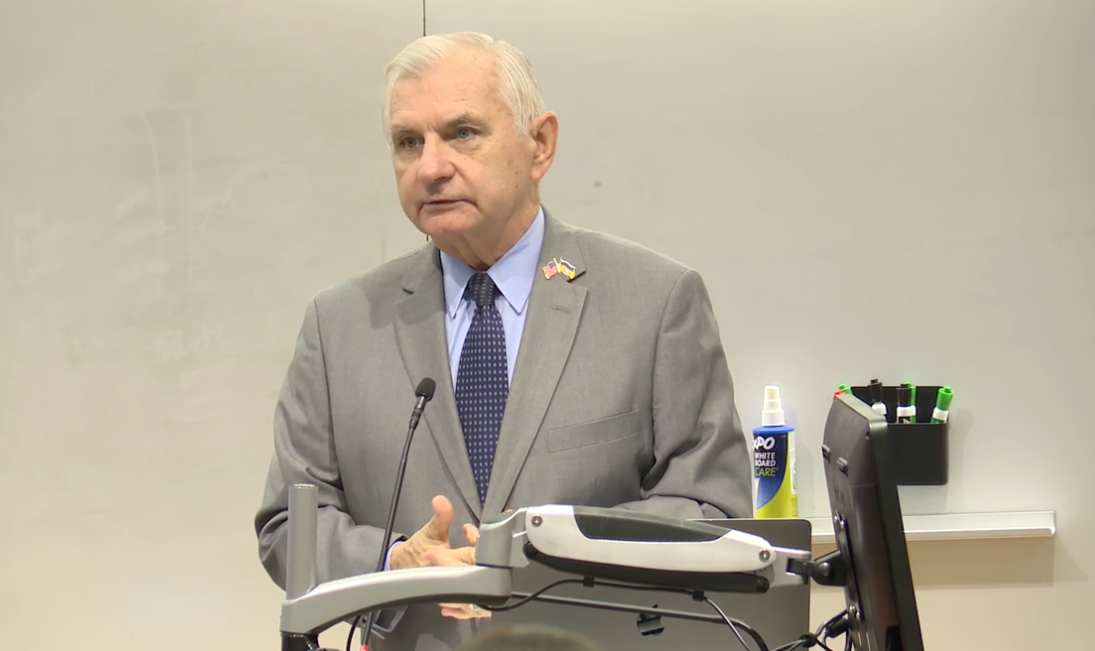

“Last year, the University of Rhode Island published a study that estimated that the top two inches of Narragansett Bay now contain more than 1000 tons of microplastics, tiny particles of broken down plastics,” said Rhode Island State Senator Jack Reed in his opening remarks. “It's built up over just the last 10 or 20 years. And these microplastics have made their way into everything including the food chain. They've been detected in all different types of species of marine animals, from plankton to commercial seafood and whales. They've also now been discovered in human beings.”

Rhode Island State Senator Sheldon Whitehouse amplified this concern in recorded video remarks from Washington, D.C. “Plastic pollution is now throughout the oceans from the bottom of the Mariana Trench to the farthest away islands and shores, even in our beloved Narragansett Bay,” he said. “It's now estimated that there are 16 trillion pieces of microplastic, adding up to maybe a thousand tons of plastic. And we have a lot of work to do to figure out what that plastic means when we ingest it, and it gets into our digestive system, brain, and organs.”

To understand the impact of plastic on the coastal system of Rhode Island, keynote speaker J.P. Walsh, professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography, collected sea floor and shoreline samples of sediment, measuring the surface concentration of microplastics for the URI study referenced by both senators. He then took cores from marshes and estuaries to examine the sedimentary record. “The cores all show this trend of very high concentrations of microplastics at the surface decreasing to near zero as we go back to sediments that are dated around 1950,” said Walsh.